Nathan Ragan

Foreword

I was born in 1946 to Robert Nathaniel Ragan and Iva Delores Wilson Ragan. I thank my father for his love of our family history and the stories he told to me. I wish I had listened better and remembered more.

My ancestral connection to Nathan Ragan of this narrative is through the lines of my father Robert Nathaniel Ragan > Jacob William Ragan > Nathaniel Francis Ragan > Nathaniel Simpson Ragan > Nathan Ragan, Jr. > Nathan Ragan, Sr.

I have tried to substantiate my reasoning for the facts and events in this narrative as fully as I could. My information, while I believe to be as complete as any that I have found to this point, is not all conclusive and it will be a life-long search to add, modify and elaborate on Nathan’s remarkable story of courage and spirit during our country’s westward expansion. I am open to research or ideas from other of my cousins that would make this narrative more compelling and accurate. I hope it will shed some light on your heritage.

The small amount of information contained in this attempt to make all of my Ragan cousins, family, sons, and grandchildren more aware of our grandfather, nevertheless represents years of research. In addition to Dad, I wish to thank my brother Ken for putting up with my “need to know” and his willingness to make the journey to Dickson County with me to complete my research. There we had the pleasure of meeting through the line of George W. Ragan (the last son of Nathan), my Ragan cousins Dale and Alan Ragan. They provided photographs for my story and were generous with their time. Alan is currently the Dickson County Historian.

I also would like to acknowledge James Hugh Ragon for his many contributions to my research through the years. I thank him also for being so gracious in proofreading the first draft of this document.

I have come to know Grandfather Nathan a little through the research and documentation. He was not a rich man. But, he provided well for those that depended upon him, and he gives me the impression of being tremendously self-sufficient, hard working, and kind. I have no doubt of his kindness, as the given name of Nathan and/or Nathaniel has continued on through virtually every generation throughout the years. I believe he was admired and respected by his family and all who knew him.

And lastly, I think he had “guts” and an adventuresome spirit.

You be the judge.

Keith Wayne Ragan

March 2011

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Nathan Ragan Years in North Carolina and Tennessee

Researched, Written and Copyrighted by Keith Wayne Ragan

My purpose for writing this narrative is not to provide the usual exclusively genealogical records for my fourth great-grandfather, Nathan Ragan, but to provide a few thoughts and insights into his life and travels as well. First, I think it is important to see the flow of events in Nathan’s life in a narrative form of timelines, including the early records in North Carolina and lead into some narrative on his life and that of his family as they made their way into west central Tennessee. I suppose many hard-core genealogists would find my way of telling Nathan’s story a bit too colorful or liberally interpreted for their personal tastes. But, I write this hoping to provide context and provoke thought to all of my fellow descendants of Nathan. I apologize in advance to those purists of genealogical detail.

There are many origin theories for Nathan Ragan. Most attribute his parentage as springing from John Riggen and wife Jemimah Dougherty of Somerset County, Maryland. John Riggen’s will there of 2 November 1773, executed 22 May 1776 mentions sons Obediah Riggen, John Riggen, and Nathan Riggen. This Nathan was born 16 August 1749 and is of the right age to be our Nathan. The problem is that this Nathan is appearing in Somerset at a time when we know our Nathan was in Granville County, NC.

Consider, the tax list for 1783 in Somerset Maryland has a Nathn. Riggen living there with 200 acres, and there are 3 males and 3 females in his household. In addition, Henry Davis of Worchester County, Maryland, which abuts Somerset County on the southeast, has a will witnessed by Nathan Riggon. In 1796 Nathan Riggin in Maryland witnessed the will of David Matthews in that place, and in 1798 John and his brother Nathan Riggin witnessed the will of Benjamin H. Matthews as well.

But, meanwhile it can be definitively stated that our Nathan Ragan is listed as a resident and is on the tax list of 1777 and 1784 in Caswell County, NC. In the 1784 census he is living on Mayo Creek. He is also on many subsequent records in Caswell and Person Counties in North Carolina between 1784 and 1804 while the Nathan Riggen in Maryland was on records that seem to substantiate his presence there. Our Nathan could not have been in both places at once.

It is generally accepted that a John Ragan is the father of Nathan. If so, we would need to substantiate that a John Ragan was in the counties of Granville, Person, and Caswell at either the time of Nathan Ragan’s birth there or very early in the chronology of his life.

And indeed records to verify John Ragan was there at the right time do exist. Both a John Regan and John Ragon are found on the 1755 tax list for Granville County, North Carolina. This may represent a father and son, and many believe it indeed does. The possibility also exists that these two John Ragans/Ragons/Regons, Riggans are related somehow, but not father and son. John Ragan in any of its derivative spellings is to the Ragan line what John Smith is to the rest of the surnames in general springing forth from the British Isles and Ireland. It is abundantly enumerated in countless records.

In “The Granville District of North Carolina 1748 – 1763, Abstracts of Land Grants, Volume II” by Margaret M. Hofmann we have this entry: Lord Granville to John Riggin – 13 Mar 1760 – 600 acres in Granville County in the Parish of St John on the north side of Watery Run, joining John Meacon, Col. Parsons, and Gidel Meacon OR: /s/ John Riggin. Wit: Will Hurst, Lawr Lancroft, surveyed 15 June 1754. scc: William Reed, Samuel Bell, Sherd Haywood. Deed survey plat reads….”surveyed for John Regan.” Note the different spellings for John Ragan in the same document.

On January 18, 1762 John Ragan is a sworn chain carrier for a survey by Thomas Person for 700 acres for Michael Wilson in Granville County.

These records alone substantiates John Ragan in St John’s Parish and Granville County in 1760 and perhaps as early, likely even earlier, than 1754.[i] [ii]

Continuing with entries for John Ragan, we find additional records for this name.

In 1769 tax records for Granville County, we have John Ragain and James Ragain. This James Ragan could be of age to be a son of John, assuming a generous timeline of John’s birth to be 1720-1730. Unless this James is recently arrived from outside the county and making the assumption of a son of John, since he is appearing for the first time we may assume a legal age of 18-21 years. This calculates to a birth of roughly 1747-1750 for James.

In 1775, we indeed do have a John Ragan JR, and a John Ragan, SR in Granville. This John Ragan JR., now head of household, would be of an age to represent a contemporary or brother of our Nathan (B: 1750-1751), and is too young to be John Ragan, the son of Nathan, (B: 1769). Assuming an age of this John of 20 years in 1775, we can estimate a birth circa 1755, and may possibly represent a second sibling of our Nathan.

So, if John Ragan, SR is the father of our Nathan as seems likely, we have proof at least of a John Ragan/Ragon/Riggan to be in Granville at least as early as 1754, and as stated previously, likely earlier. This seems to point to a very early childhood, if not birth, for our Nathan in what was then Granville County, North Carolina. The Person County of today would have been included within Granville’s boundaries in 1746-1752.[iii]

Nathan’s first male child is believed to be John, born 1769 and would make Nathan’s first marriage to an as yet unknown spouse prior to 1769. Most men of the day were expected to be 18 years of age to marry, so we may presume an approximate birth year of Nathan again circa 1750-1751. It appears his first- born, as was the custom of the day, was named for Nathan’s father, John.

The 1777 North Carolina Census and the North Carolina Early Census Index have our Nathan Ragon living and head of household in the Nash District of Caswell County, North Carolina.

In 1784 we have Nathan Ragon in Caswell County, 150 acres on Mayo Creek. Note: Mayo Creek flows out of Halifax County, Virginia across the border today to Person County, N.C. and is mostly submerged beneath the waters of Mayo Reservoir. Mayo Reservoir is N.E. of Roxboro, N.C.

Before continuing the records for Nathan Ragan in Caswell and Person Counties of the day I would like to inject a bit of historical color relevant to the decade of the 1780’s. The Revolutionary War was in full steam in this period of the genealogical record. At one point General Cornwallis brought the bulk of the British army storming through Caswell County on a route that took him into Virginia by way of Leasburg and Semora, not too far from Nathan’s homestead. Military historians regard this a major, if not the major turning point in the Revolutionary War; for General Cornwallis was hot on the trail of the crafty U.S. General Greene who was feigning a retreat in order to draw the British forces further and further away from supplies and reinforcements. Historically, this ploy by General Greene is referred to as “the Race to the River Dan.” You just know tensions were high in Caswell and Person during this time in American history. All local militia would have been activated. Nathan, a man in his early to mid-thirties, was likely, almost certainly, among them. I have yet to substantiate this by record.

In 1790 we have Nathan Ragon on the tax list for Granville County. I believe this represents not relocation for Nathan, but a shift in the county boundaries. Please see footnotes at bottom of this narrative.[iv]

In 1792 Nathan Ragon is on Person County taxpayer list, Nash District, with 163 ¾ acres. No slaves. Again, he has not relocated, but county boundaries have once again shifted.

In 1793 Nathan Ragen is a taxpayer in Person County.

In 1794 Nathen Ragoon has 166 acres in Person County.

In 1795 Nathan Ragan is a taxpayer in the Nash District of Person County.

13 April 1795, Nathan Ragan sold 166 acres “where Ragan lives with mill” in Person County for 131 lbs to John Baird of Prince George County, VA. A note here: The area in which Nathan lived was generally known as the birthplace of bright leaf tobacco. The demand for tobacco in England and in the colonies was great and the growing of it lucrative for the citizens of Caswell and Person Counties. But I do not find records that indicate that this was a primary endeavor for Nathan. The mill would seem to suggest that he was a general farmer and perhaps ran the mill to grind corn or wheat for his homestead or even to capitalize on the enterprise and perform the function for the local citizenry.

23 April 1795, “James Wilson to Nathan Ragan for 100 pounds 200 acres on Mayo adj. Lewis Parrot, Gabriel Davie (Davey) – it being remainder of tract surveyed by William Waite for Wilson.” Nathan has relocated.

In 1800 Nathan is not on a tax list for Nash District in Person County. He is now on the tax list in Hillsborough District in Person County. He has two males aged 10-15 in household (Lewis B: 1789 and Nathan, JR B: 1787), 1 male 16-25 (Jesse B: 1775), and 1 male +45 (Nathan B: between. 1750 -1755). John (B: 1769 and William B: 1773) are obviously out of the household. There are females in the household as well: 1 female aged 10-15 (Nancy Ann? B: 1788), 1 female aged 26-44 (unknown, possibly Elizabeth), and 1 female +45 (quite probably Nathan’s spouse - unknown).

Many of our family researchers have laid claim to Elizabeth Ray (Griffin) as the spouse of our Nathan in North Carolina. It is my opinion that this is not only unlikely, but also impossible.[v] Elizabeth Ray did marry a Nathan Ragan just not our Nathan Ragan. Female given names that appear in future generations are quite common for the day, and include Jemima, Nancy, Catherine, Elizabeth, Martha, Jane, Ann, and Sarah. Perhaps one represents a namesake for our ancestral grandmother. But I do not find at the time of this research anything to confirm the given and maiden name of our ancestral grandmother.

In that same census of 1800 there are two female “Ragins” listed as head of household, Martha and Patsey. Patsey is of interest since she is a young widow apparently, and is enumerated only one household removed (John Wilson) from Nathan. There can be little doubt of a connection to Nathan.

Patsey is 16-25 years of age (born between 1775-1784), with one son aged 10-15, 1 son <10, and 3 daughters <10. Could this be the widow of one of Nathan’s sons? John is not listed on the 1797 census in Person County but William (1 free poll and no acreage) and Jesse (1 free poll and 178 acres) are. The last census in Person County that would appear to be John, son of Nathan, is 1794. From whom is young Patsy widowed? It appears likely that this would be John, and signals an early death for Nathan’s oldest son.

Let’s continue with what the written record gives us for Nathan Ragan, Sr. From Person County Land Grants: Jones, Samuel 70 acres, Dec 5, 1801, on Tar Road next to Nathan Ragan.

From Person County Land Grants: Ragan, Nathan 36 ¾ acres, Dec 16, 1803, on Tar Road adj. Samuel Jones. CC Ashburn Davey and Josiah Wade. Tar River Road today runs south off of Highway 15, south of Creedmoor to Falls Reservoir. If this is the same Tar Road of this land grant, does Nathan now own land in two separate locations?

March 5, 1804: Nathan Ragan to Jesse Ragan, for 13 lbs, 50 acres adjoining Gabriel David(Davey), decd, Doctor Syms. This deed void if Jesse Ragan sells land while grantor still lives. Acknowledged in open court. (This is likely Nathan’s son, Jesse as proved by the next entry.)

April 17, 1805: Jesse Ragan JR to Nathan Ragan for $85, 50 acres adj. Sims, Davis(Davey). Wit: Ashburn Davey, William Street. (Jesse now returns the land to his father. It is possible that the 50 acres was a part of Nathan’s 200 acre homestead and that this return to the original parcel was paving the way for liquidation of Nathan’s properties before his journey from North Carolina.)

May 28, 1805: Nathan Ragan to Swepston Sims for 200 lbs, 200 acres on Mayo adj. Samuel Jones and said Sims. Wit: Ashburn Davey & William Street.

August 12, 1805: Nathan Ragan to Ashburn Davie (Davey), for kindness rendered, 31 ¾ acres on Tar Road adj. Samuel Jones, Person Davie. Wit: Sweptson Sims, Samuel Self. I believe a transcription error has occurred. This “gift” represents what Nathan previously received as a land grant. It probably should read 36 ¾ acres.[vi]

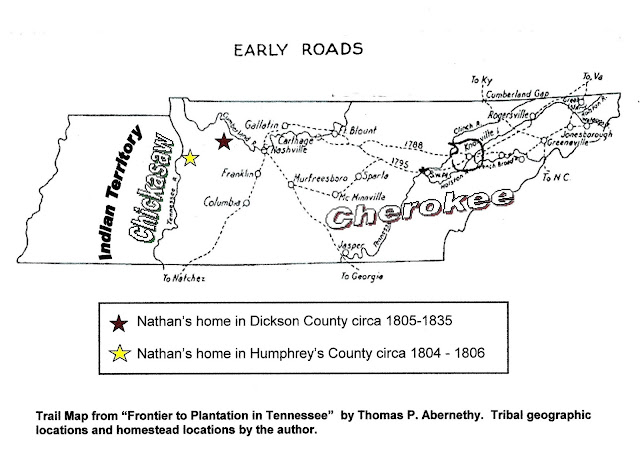

The selling of the lands in Person County coincide with the what history tells us about the relocation of Nathan to Tennessee. According to “Goodspeed’s History of Humphreys County, Tennessee”: “Those settling on Big Richland Creek about the same time (1800-1805) were William Fortner, George Turner, John Toller, Nathan Ragon, and Maj. John Burton.” This would place Nathan and sons, certainly Lewis and Nathan JR, in an area today represented by Big Richland Harbor on Kentucky Lake. The original creek, now much of it submerged below Kentucky Lake’s waters, would have merged with the Tennessee River.[vii]

At the present time we can only suppose at the difficulty of a journey from North Carolina to what was the “wild west” in then western Tennessee. It was only a canoe ride across the Tennessee River to lands not then within the borders of today's state of Tennessee, lands designated as Indian Territory. It would have been a hardship beyond our comprehension. There were rivers and streams to ford, mountains and ravines to navigate, and all the while due vigilance for hostile Indian warriors and cutthroat outlaws. This was a journey that only men well armed need make. It would have necessitated packing not only the tools needed to carve out existence in the new lands, but provisions to carry them on the journey. Foraging and taking game along the way to provide sustenance would have been a daily part of life on the trail.

I believe it likely that Nathan’s would have been but one wagon of several different families making this tremendously difficult expedition to the Cumberland Settlements. From what I have been able to read and research it is my best guess that he set out from Raleigh on what would be known as the Jonesborough (Jonesboro) Road west on to Jonesborough, Tennessee. The Road was finished from Jonesborough through the Cumberland Mountains to Nashville on September 25, 1788. The routes shifted frequently. By the time Nathan made his journey, the preferred route would first be to a location just to the south of Knoxville. The Walton Road South of Knoxville led west to a south fork generally referred to as Emery Road. This would be in the area of today’s Crossville, Tennessee. It was the newer route, established in 1795, and also known as the Avery Trace (Southern Route) to Nashborough. This route was being referred to as a turnpike circa 1804 and during Nathan’s sojourn, and was often referred to as the Cumberland Road or the Great Stage Road in later years.

The road itself the Cherokee believed was in violation of their territorial boundaries and of treaty, and it was not uncommon for them to unleash attacks upon those daring to make use of it. It followed closely in some sections their own “Tollunteeskee’s Trail”. The “cutting” of roads in Cherokee land without payment was one of the primary reasons for a long and bloody war between the white settlers and the warriors of the Cherokee nation.

The Cherokee hostilities were common when Nathan’s group made their laborious traverse along the dirt path, now in some sections twelve feet wide. Militias were few and sparsely dispersed along the 185-mile trek. The various groups of wagons would assemble at the junction of the Clinch and Tennessee rivers until they felt there were sufficient numbers to repel attacks. And it is impossible to conceive that the weary travelers did not meet the same savage assaults as those preceding and following their particular caravan. But their arrival at long last in the Cumberland Settlements did not mean safety or that life would be easier. Indeed, the adventure had just begun!

Arriving in Humphreys County, Nathan and the family were immediately greeted with hostilities from the Chickasaws. Many historians view the Chickasaws as the most fierce of the tribes east of the Mississippi. This also from Goodspeed’s notes for the early years, “From the first days of settlement (Humphreys County) up to the year 1812 the Indians were a source of great annoyance and trouble to the whites, and raids were made by hostile savages upon the settlements frequently, when the houses of the settlers were burned and their stock run off. In not a few instances the lives of the settlers were sacrificed in defending their families and property. The Indians had several large encampments in the county, the leading ones being on the Tennessee River, about two miles below Duck, at Hurricane Rock Hill, and on the hills around Paint Rock, both of the latter being on Duck River.” A number of settlers were murdered along with their families up until at least 1815 according to the writings of Goodspeed. The Chickasaws were removed across the Tennessee River about 1810-1811 but “Long after the removal of the Indians across Tennessee River they continued their depredations, and it was necessary that the eastern shore of the river be constantly guarded by rangers. The settlers would take turn standing guard.” What the early writers of the day did not acknowledge, was that for a time prior to the settlements 1800-1805 many injustices were also done the native Americans, from murders, treaty infractions, to bounties for Indian scalps.

It is no wonder then that Nathan, a man of about 55 years of age, took the family from Big Richland Creek and relocated some few miles east in Dickson County on Bear Creek between winter 1805 and early spring of 1807. Dickson County had been settled about 10 years prior to Humphreys County according to Goodspeed. There may have been Indian troubles there also, but more neighbors to discourage the raids as well, and an additional twenty to twenty-five miles to a retreat across the Tennessee River for raiding warriors. There would need to be vigilance even at the new homestead in Dickson for another seven or eight years though, to be sure. Not, just vigilance for raiding Chickasaws, but one must always remember that this was a wild and untamed country in general. Northern bands of Creeks, called Redsticks (designated by the Indians themselves as clans at war with the whites and their allies) also are known to have forayed into Tennessee seeking captives and plunder during these years, especially 1812-1815 during the War of 1812. And Bear Creek was not so named because of the local squirrel population. To use the jargon of the day, black bears were “thick.”

Indeed, the Tennessee that Nathan entered at the turn of the 1800’s would not resemble the Tennessee of today. The forests were of huge trees, widely spaced with little to no undergrowth. According to family stories thought to have originated with Nathan, "one could easily drive an ox cart and team through the sparsely populated virgin forests of the day". The fauna included now extinct rookeries of passenger pigeons, much preferred for their meat, and Carolina Parakeets added color to the majestic canopies. Packs of gray wolves were common, and a nuisance to livestock, as well as a danger to solitary hunters in mid-winter. Males of the species were commonly 120 pounds and could reach weights of over 150 pounds. They would not become extinct in Tennessee until about 1850. The smaller species of red wolves, the males topping out at around 90 pounds, also competed with their larger cousins for deer, elk, and the eastern or woodland bison, before also becoming extinct in Tennessee before the turn of the twentieth century.

The bison were once present all the way to Virginia, but were few in number compared to their plains counterparts. The famous Natchez Trace was a much-used pathway from Nashville to Natchez, Mississippi. Before it was a pathway for Native American tribes, it was a migratory route for the bison when they moved south to their winter range. Elk were common; a source of sustenance in the early days, and the last elk killed in Tennessee met its demise west of Dickson in Obion County in 1865.

It is well documented that Nathan, certainly with Lewis and Nathan, Jr. (my third great-grandfather) in tow, purchased 200 acres of land from Ezekiel Norris near Vanleer east of Yellow Creek[viii] in Dickson County on December 3rd, 1805. The deed states that the property was part of a land bounty from the state of North Carolina to Colonel William Davis for his military services, and deeded down to Ezekiel Norris. The court required Ezekiel Norris enter the proofs of ownership into record. They were proven in the January term of 1807 and registered on May 29th, 1807.

|

Pages 1 & 2 of Nathan's land purchase in Dickson County, deed and entry record. Documents provided by Dickson County historian, Alan Ragan to the author. |

As of this writing the property has a little log cabin still standing, perhaps 15 feet square with a stone chimney and fireplace. I am convinced that it would have housed whatever number of Ragans that was still in the family group for considerable years. It is not known for sure, but the cabin could have already been there at the time of the first occupation, or it would have made for a hard first winter in the valley beside the waters of Bear Creek. But, just perhaps, the demonstrated fortitude and perseverance and pioneer spirit of Nathan and the boys endured the hardships of winter’s climes, and the little log cabin was their handiwork.

In the copy of the original deed provided me by Alan Ragan, Dickson County Historian, granting Nathan the property for 150 silver dollars in hand, it does not specify a residence, only the land. My belief is it is indeed of Ragan origin, since a dwelling is almost always listed in a deed of the time. It is not hard, regardless of the cabin’s origins, to imagine the family huddled around a wooden table, the fireplace generating enough heat to make the cabin cozy, eating a meal of venison or squirrel stew, the winter wind howling like angry Chickasaw warriors around the rough hewn timbers.

The younger sons of Nathan still with him at the homestead in 1807 would begin leaving the farm and beginning families of their own in the years of 1810-1815. In 1810 Nathan JR (born 1787) would marry Catherine Young, daughter of South Carolina Revolutionary War hero Captain William Young in Dickson County. Captain William Young began journeys from South Carolina “because there were too many people” around 1807. At one point he lived in Christian County, Kentucky and had the family in Dickson County, Hardeman, and Perry counties at various times. William Young died in Perry County at 93 years of age in 1837. A stone crypt sits on a hill marking his place of interment with the words “Revolutionary War hero”.

Many Tennesseans would serve in the War of 1812. Some would join General Andrew Jackson’s forces in the flotilla to New Orleans to confront British regulars. But, for most of the Tennessee men in the “the second war of independence from Great Britain”, the war entailed service with “Old Hickory” in the Creek Wars in Alabama and some in the Seminole Wars in Florida. The northern Creeks were aligned with the British in engaging American militia throughout the Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama regions during the time span, necessitating occupation of American resources and soldiers in the arena and preventing them from being used in the adjacent areas of British campaigns.

The Tennesseans that served in the militia were not usually of the pomp and regalia of the regular army. They were, for the most part, not uniformed, and furnished their own horse and weapons. They were citizen soldiers, with farmsteads and families that depended upon them for sustenance and survival. Leaving home at a time when hostile enemy warriors were raiding homesteads was a great sacrifice to make, even though makeshift militias of those not making the march into Alabama were left behind. But, these were rugged backwoodsmen, and their skills and ability to survive off of the land were instrumental to Jackson’s campaign as they answered their patriotic call to duty. The quicker they “got the job done” the quicker they could return to family and hearth. Most all of these men were signed to serve 6 months duty, understanding that families back home could not long survive without them.

Both Nathan JR and Lewis would serve in the War of 1812, Nathan JR fighting in the Creek Wars in Alabama, primarily in the vicinity of Mobile, and was likely serving with Andrew Jackson’s forces under Colonel Alexander Loury in the talking of Pensacola from the Spanish on November 7, 1814. He was in the 2nd Regiment of the West Tennessee Militia[ix] in Captain James Kincaid’s infantry as a Private. In addition to casualties of war Nathan’s unit was hit extremely hard by disease.

Lewis received land grants in New Madrid, Missouri for bounty for his service in the war, and he lived there for a short time before returning to live out his years in Humphreys County. He served as a Private under Captain Joseph Williams in the Militia Cavalry.

Nathan’s sons William and Jesse, independent heads of household, likely did not accompany him on the initial journey to Tennessee, but would join Nathan in the immediate ensuing years in Dickson County. They also would serve in the War of 1812. Page 700 of “Tennessee Cousins” by Worth S. Ray lists William Ragan under early militia officers of Dickson County. In 1810 he is listed as an Ensign of the 25th Regiment of Light Infantry of Tennessee.[x] But, the only William Ragan from Dickson that could have served from a Dickson County militia unit during the War of 1812 was enlisted as a Private under Colonel R.C. Napier and Captain Drury Adkins in the 1st Regiment of West Tennessee Militia. This unit served Jan 1814 – May 1814 and mostly performed guard duty at Fort Williams, Alabama in the Creek Wars. They did march to Hickory Ground near Montgomery, Alabama after Jackson defeated the Creeks at Horseshoe Bend, Jackson expecting another confrontation there that never came. Horseshoe Bend was the beginning of the end for the Creek Nation in the War of 1812.

Jesse Ragan represented the citizens of Dickson County in the War of 1812 while serving under Colonel John K. Wynn and Captain Bailey Butler, 1st Regiment West Tennessee Militia, Oct 1813 – Jan 1814. His unit was present at most of the battles of the Alabama Creek Wars including Talladega, November 9, 1813.

Before I return to Nathan SR in Dickson, I would like to speculate on one additional Ragan in service of Dickson County during the War of 1812. If the Patsey Ragan discussed previously on the 1800 census of Person County, North Carolina did represent the widow of John Ragan, son of Nathan SR., then it seems likely that we have another John Ragan unaccounted for.

For, in the regiments formed from men from and surrounding Dickson County in the War of 1812, I find John Ragan, Corporal under Colonel Robert Dyer and Captain Thomas Jones, Volunteer Mounted Gunmen (Cavalry). This unit served Sep 1813 – May 1814, and was in almost all the battles of the Creek War, including Talladega and Horseshoe Bend, March 27, 1814. This unit had the distinction of serving, as they were called at the time, as “spies” leading the marches for Andrew Jackson’s forces and performing reconnaissance along the way. They were always in harm’s way.[xi]

One can only imagine the prayers and mental anguish of a father like Nathan, with so many sons in active service during wartime; and the tears of a mother, if she still lived, as well. The homecomings, solitary riders coming down the dirt road by Bear Creek, small at first until clarity and certainty confirm the familiar forms and faces --- the elated cries of joy and torrents of tears can easily be imagined by those having more than just a passing interest of the data and graphic record.

All of these proofs of service can be found in the book “Tennesseans In the War of 1812” transcribed and indexed by Byron and Samuel Sistler. The book has foreword that includes this note: “Almost all the men named herein, were involved (War of 1812).” The Tennessee State Government website http://www.tennessee.gov/tsla/history/military/1812reg.htm provides regimental histories.

Returning now to Nathan SR., by 1820 Nathan JR is in Hickman County, Tennessee with his family. Lewis is now in Humphreys County, possibly on the original Ragan Tennessee home site that had been abandoned during the hostilities with the Chickasaws. Jesse and his family are still in Dickson, and William lives with family in Dickson County but not with Nathan beside Bear Creek.

If the John serving from Dickson or surrounding counties in the War of 1812 was the son of Nathan as seems unlikely, he either did not survive the war, or is relocated. He is not listed on the census for Dickson or surrounding counties in the aftermath..

It is also quite certain that Nathan’s first wife, if she was alive after the 1800 census in Person County, North Carolina and made the pilgrimage to Tennessee, was now deceased by 1820. She is in all likelihood one of the first Ragans buried in the Ragan Cemetery in Dickson County beside the log cabin. The winters would have seemed much longer and much colder, after the death of Nathan’s first wife, and until a time when the cabin would again be filled with the laughter of children, and the loving embrace of a second wife.

The August 7, 1820 census for Dickson reveals that Nathan had in the household 2 male children under the age of 10, 2 male children 10-16, 2 males 16-18, 1 male 18-26 and one male over 45 (Nathan SR). And the house now has one female aged 26-45. This coincides with the well- documented account that appoints Nathan as guardian to the children of his second wife, Elizabeth Sallie Moore (B: 1782 in NC; D: 1862 Dickson CO., TN.), recently widowed from Robert Rogers. The males in the household of the 1820 census are Jesse, Callum, John, James, Robert, Henry R., and Edward Moore Rogers, all sons of the female in household, Nathan’s second wife Elizabeth Sallie Moore, Robert Rogers widow.[xii] There is 1 male slave aged 26-44 at the homestead and he likely came with Elizabeth and the boys to their new place of residence. This man along with Nathan and two of the older boys are listed as engaged in agriculture.

At the time of his second marriage to the younger Elizabeth, Nathan SR would have been 70 years old and yet was about to father another family.

Sometime around this period of time it is to be surmised that Nathan, by necessity, built the second rough hewn house, this one two story, from timbers on the homestead situated at a right angle to the original tiny log cabin. This home no longer exists, but photos support it still remaining as late as 1890. Plenty of young men were available now to man the saws and axes, chains, and skids, and sleighs for the arduous labors involved in cutting the timber, dragging and hauling it to the saw mill to be split into rough slabs. Or perhaps Nathan, the male slave, and the sons of Elizabeth were able to convert the timber into finished product right on location.

Nathan and Elizabeth had three sons by their own union: Moses born 1823, Washington born 1823 (twins?), and George Wilson Ragan born 1825, and dying in Dickson County in the year 1914. George Ragan would continue on at the farm on Bear Creek for some years, mother Elizabeth living with him and enumerated on the 1860 census, though it is not clear if it was on Bear Creek. But, it is likely it was. Elizabeth would though, be still living at the homestead with son James Rogers in 1850 according to the census that year for Dickson. James left the homestead prior to 1860, when he is found on the census for Graves County, Kentucky. Moses would be in Davidson County in 1850, relocate to Cheatham County for a time, and return to Davidson County where he would pass away sometime after 1891. He notes as I have always suspected, that his father (our Nathan) was born in North Carolina on the 1880 census.[xiii] Washington Ragan would be deceased by 1846.

The years after Nathan’s second marriage on the little farm were prosperous for the place and time. Perhaps prosperous paints the wrong image. The family had land that abundantly produced fodder and grain, principally corn and oats. Livestock included at least one yoke of oxen to perform the heavy work, and there were horses for riding and a number of cows for milk, cream and butter as well as for an occasional butchering. Sheep were kept for carding wool to make clothing and Elizabeth had a loom and woolen and flax wheels. Large numbers of hogs were always kept to ensure adequate winter meat, perhaps up to a hundred head or more at any given time. There were always chickens, and geese were important for down as well as for their fat and meat. Abundant deer and an occasional elk provided venison, and small game and fowl would always be a supplement to the daily menus. The cool waters of Yellow and Bear creek yielded recreation, and bass, sunfish, and catfish as well.

The 1830 census reveals that there were lots of hands available to make the farm productive. The slave had been sold, granted his freedom, had died or escaped for he was not enumerated on the census. Nathan and Elizabeth’s 3 sons show up in the 5-9 age group. Elizabeth’s children from the first marriage to Robert Rogers are still well represented. There is 1 male 10-14, 1 male 15-19, 2 males 20-29, and Nathan listed in the 70-79 age group. This would again seem to support a year of Nathan’s birth circa 1751. Of the females, there is 1 aged 15-19 and probably a wife to one of the Rogers boys, and Elizabeth aged 40-49. Having another female on the premises to help feed and care for all the men must have been a tremendous blessing for Elizabeth. And with all the boys growing into men, perhaps Nathan didn’t have to work quite as hard during these years, and there can be no doubt that his was not a lonely life in the silver years of old age.

Nathan was born prior to there being a United States and was of an age, mid-thirties, to serve in the Revolution. There was virtually no man in North Carolina at the time that did not serve at least in some local militia. But, we find to date no existing record to document his service. Nathan was of Irish ancestry, substantiated by the author's DNA record as well as ingrained in family oral history, and there can be little doubt of his allegiance to the new nation at war and for it’s independence from Great Britain.

At life’s leisurely pace, after many perils that cannot even be imagined by family historians of today, through many miles of wilderness, the years had taken Nathan from the fertile soils surrounding the waters of Mayo Creek in North Carolina, to rest on the hill beside Bear Creek in Dickson County, Tennessee.[xiv]

Nathan Ragan SR died on February 2, 1835 at approximately 85 years of age and an inventory by the administrator, his widow Elizabeth Ragan, recorded sale of his estate on February 19, 1835 in Dickson County. No record of final settlement has been found or been made known to this descendant. The inventory of the property belonging to the estate of Nathan Ragan included many items that help to paint a more complete picture of life of the day. To work the farm there were two plough shares, two pair of andirons, augers, plow gears, clevises, log chains and sleighs, a variety of saws, chisels and adzes, various broad and other axes, grubbing hoes, wedges, planes, and jointers. Two horses were inventoried and both a male and female riding saddle. Domestic items included candle molds, a spice mortar, two meal tubs, one pickle tub, one fat stand, assorted barrels and tubs, a coffee mill, and the dishes, china, and eating utensils. Furniture and stoves included four beds and five bedsteads, a clock, two chests, a loom, two ovens, eight chairs and four tables. There were a number of iron kettles, pans, pothooks, washing tubs, and pails. At the time of the inventory, in addition to 60 head of hogs, there was fifteen hundred pounds of pork in the smokehouse.

Other animals on the homestead at the time of the inventory of Nathan’s estate included 8 cows, 1 yoke oxen, 10 sheep, and 18 geese. Harvested and stored from the fields were 75 barrels of corn, 1200 sheaves of fodder, 2 additional stacks of fodder, and 4 stacks of oats. The family and working animals of the farm were well provided for.

I will not elaborate on the previous legal action filed April 1846 by Moses, George W., (Washington was already deceased), and Elizabeth making exclusive claim to the farm left behind by Nathan, except to say this: there is inference to a previous will lost by the clerk of court according to the plaintiffs, that justified this request of exclusive ownership, that it was Nathan’s wish. There is a possibility that Nathan somehow provided for his heirs from his first marriage by means other than land and or estate property exchange. There is also possibility that Nathan felt his previous heirs were well established and did not need additional stipend, but wanted to make sure Elizabeth was provided for. But, there is also the possibility that the children that accompanied Nathan on his long journey of peril from North Carolina, survived Indian raids, possibly helped build the first cabin and establish the farm, were excluded unjustly from their rights to portions of the 130 acres on Bear Creek.

As a footnote, I made the trip with my brother Ken Ragan to see the little log cabin. At some point the original cedar shingles of the roof have been replaced by rusting tin. Aging square white pillars support the front porch roof. They stand in place of the original cedar or white oak posts. And sometime in the twentieth century an ugly green siding has been placed over the mortise and tenon joints and massive logs that are the “bones” of the little cabin. It’s a family treasure that should have more designation and dignity in its old age. As is, its days are numbered.

Nathan’s cabin is positioned but a few feet off a narrow paved road running parallel to today’s Bear Creek. The front door faces the road, and in but a few short steps one can leave the entrance portal, be across the road, standing next to a steep drop to the creek. Just to the right is a well- worn path that allows access to what have must been a spring flowing from underneath the hill. I have done enough family research, visiting the old places, that it was not hard to envision a spring- house to cool milk and churn cream into butter in the immediate proximity. This branch of the creek was dry on our February visit, but there still remained a stone trough formed probably by Nathan’s own hands to catch the cool water seeping from underneath the bank. Crossing the now dry bed of the first creek immediately connecting to the mentioned spring, twenty paces away there is a second creek branch. This one is the primary Bear Creek tributary, and its boulder- strewn bottom is clearly visible underneath the gurgling waters, in places substantially deep.

Facing the cabin, the stone chimney now tilts a bit on the left side. A small access path runs but a few feet away to the cabin’s left and up a gentle sloping incline to the Ragan cemetery. Just across this path, the second house, now no longer standing, would have been at a right angle to the little log house, it’s front door facing the stone chimney.

The Ragan Cemetery is nicely kept, the black wrought iron arch entrance connected to and surrounded by a chain link fence. George Wilson Ragan and both of his wives have a stone slab covering the entirety of their graves and their names were written in cursive while the concrete was still wet. And there are other graves clearly marked as well with other surnames. But, a great many graves surrounding George’s are marked by simple limestone slabs from the surrounding hillside standing upright at various angles. Somewhere close-by to George’s I’m sure, one of those slabs of flaking gray stone, marks the grave of Nathan, and next to him possibly his first wife, and certainly of his second, Elizabeth.

It was an emotional experience for me to finally come to a place so full of the spirit still, of my fourth great-grandfather. I take literary license here, and those purists of detail and record may feel free to take my following flight of fancy as nothing more than the ramblings of an aging Ragan descendant caught up in the moment

On that cool but pleasant February afternoon I stood there reflecting on Nathan in Ragan Cemetery, in the area of his interment on the rise above the cabin. I came to the conclusion that he was a rather extraordinary ordinary man. And I quietly thanked him for his courage and his perseverance, and his pioneer spirit. Then, as I shifted my attention from my 4x-great-grandfather’s place of rest, I looked down the slope of the hill towards the cabin, and the passage of the years melted away. I could easily imagine another time on the quiet hillside when the laughter of children echoed across the valley, and bare feet scattered the hens and geese looking for handouts. Being a father and grandfather myself, I could envision Nathan’s lips turning upward with a slight smile, watching the spectacle of the children at play, from the porch.

And I allowed my imagination one more fanciful pause as I conjured the image of Nathan’s gray hair and beard, betraying the youthful twinkle in his eyes, exhaling smoke from an old clay pipe. The translucent wisps curled and vaporized in the chilly air of Bear Creek.

Copyright March 4, 2011 by the author, Keith Wayne Ragan. This narrative and the art and photos are intended for family collection and use of the descendants of Nathan Ragan, and no portion of the narrative including the photography may be be reproduced and/or published without the written consent of the author.

Copyright March 4, 2011 by the author, Keith Wayne Ragan. This narrative and the art and photos are intended for family collection and use of the descendants of Nathan Ragan, and no portion of the narrative including the photography may be be reproduced and/or published without the written consent of the author.

Footnotes

i In 1760 St John’s Parish included all of Granville County. In 1761 Granville County was divided into two Parishes; the western half of Granville became Granville Parish and the eastern half became St. Johns Parish.

ii In 1764 the eastern half of Granville County (St John’s Parish) became the bulk of newly formed Bute County. I mention this only because many genealogists exclude Bute County when researching roots of our lineage. This clearly demonstrates that we may have John Ragan of Granville County in 1760 in what was to become Bute County (existing from 1764-1779). After that time, Warren County absorbed most of Bute.

iii A word about the various counties of record in North Carolina for our Nathan; Granville was the county of most early records for our Ragan/Ragon/Riggan line. Orange County was formed from parts of Granville, Bladen and Johnston (now Wake) counties in 1752. Prior to 1770 Orange County took in all of present day Orange, Caswell, Person, Alamance, Chatham, most of Durham, small parts of Wake and Lee and the eastern 1/3 of Rockingham, Guilford, and Randolph Counties. Bute County was formed from Granville County in 1764 and abolished in 1779 when it was divided into Warren County and Franklin County. As counties formed and others changed boundaries and even others eliminated, the records for Nathan Ragan appeared in several different county records.

iv It is truly a confusing time for genealogists and family historians because the county designations changed frequently during the mid-late 1700’s. Our principal counties of concern for Nathan’s story are Caswell, Granville and Person; so let me attempt to simplify things a little. Or not. In 1746 –1752 Person County of today was included within the boundaries of Granville County. From 1752-1778 it was included in Orange County. From 1778-1792 it was part of Caswell County. Caswell was established in 1777 from Orange County. Person County was established in 1792 from Caswell County as a permanent county in North Carolina. You can see the difficulty in trying to associate places and timelines to our ancestry in this area

v Elizabeth Ray was born in Virginia on September 18, 1750 to John Ray and Susannah Vance (Salsbury) Ray. She married John Griffin before 1770 and John died in 1780. She re-married the Nathaniel Ragan of Lincoln County, Georgia in 1785. This Nathaniel Ragan was the son of Jonathan Ragan of Nottoway County, VA, born 1744. Jonathan Ragan was a Revolutionary War soldier serving in the Georgia line under General Elijah Clarke. He died in Washington County, Georgia on April 6, 1813. Nathaniel died in 1831 in his native Georgia. It’s once again a case of our Nathan Ragan not being able to be in two different places at the same time. Our Nathan could have not been married to Elizabeth Ray.

vi I am curious as to “the kindness rendered” by Ashburn Davey. Ashburn Davey was born in 1772 and was some years Nathan’s junior. He was the son of Gabriel Davey and Elizabeth Bumpass (Davey), a very wealthy and prominent family. Gabriel Davey died prior to 1797 but Elizabeth, and it appears Ashburn living with her, are on the 1797 Person census with 1661 acres and 9 slaves. He would either accompany Nathan to the Cumberland Settlements or follow him shortly thereafter. He is found just to the Northeast of Nathan’s homestead in what would become Stewart and Houston Counties. He would marry Elizabeth Winstead and die in Houston County in 1829.

[vii] It cannot be doubted that a trip to the land in Humphreys County would have required a previous trip, either by Nathan – or more likely one or more of his sons – to scout and purchase the site of the new homestead. This could have been John, again, it seems unlikely, which could explain his absence on the 1800 census in North Carolina. John would have been about 31 years old in 1800 and capable of making the journey, safeguarding the monies with which to procure new properties, and as the oldest son entrusted with the interests of the family.

viii The deed specifies east of Yellow Creek. The branch that flows out of Yellow Creek eastward was to be later specified as Bear Creek. Nathan’s property and cabin is on today’s Bear Creek north of Bear Creek Road, a short distance east from the main Yellow Creek channel.

ix The area of the Cumberland Settlements located in the vicinity of Nashville and east of the Tennessee River was then West Tennessee. West of the Tennessee River was Indian Territory.

x William J. Nesbitt further substantiates this in his book “The Primal families of Yellow Creek Valley”. The information is from the notes left by Mrs. John Trotwood Moore, wife of the former state historian of Tennessee. This militia unit, the 25th regiment of Light Infantry, was organized primarily to defend against Indian raids in the settlements.

xi Interestingly enough, Ashburn Davey appears as a private serving along with the unidentified John Ragan in this regiment in the War of 1812.

xii Robert Rogers came to the Cumberland settlements from North Carolina and was a soldier in General Jackson’s army in the New Orleans campaign. He made it home from the war but like many veterans perished shortly after his return from the campaigns. Several historians document there were widespread epidemics and sicknesses based on mortality schedules in the immediate year(s) after the campaign in the Deep South in the Creek, Seminole, and New Orleans arenas of war. Robert Rogers died July 15, 1815. His estate settlement was finalized from will on April 3, 1820.

[xiii] George Wilson Ragan also notes North Carolina as the place of birth for his father, Nathan, on the 1900 census. This should put to rest any Maryland origins for this Nathan Ragan line.

xiv My distant cousin and fellow family researcher, James Hugh Ragon, commented after reading my narrative, that Nathan and son, George W. Ragan lived and witnessed 163 consecutive years of America’s history including the French and Indian War, the American Revolution, The War of 1812, The War with Mexico, The Civil War, The Spanish-American War, and the beginning of World War I. Their life spans began in 1751 and concluded in 1914.

I am a distant relative. Judy Hughes Tussy is my mother. Her mother was Amanda Lou Ragan Hughes. Her father was Solomon Dixon Ragan. His father and mother were Sarah Rachel Turner Ragan and Joseph Wesley Ragan. Joseph's father, I believe was William Ragan and his father was Nathan. Thanks for this beautiful narration and history research! Do you have any information on Nathans son William, who followed Nathan from North Carolina to Tennessee?

ReplyDelete